Introduction

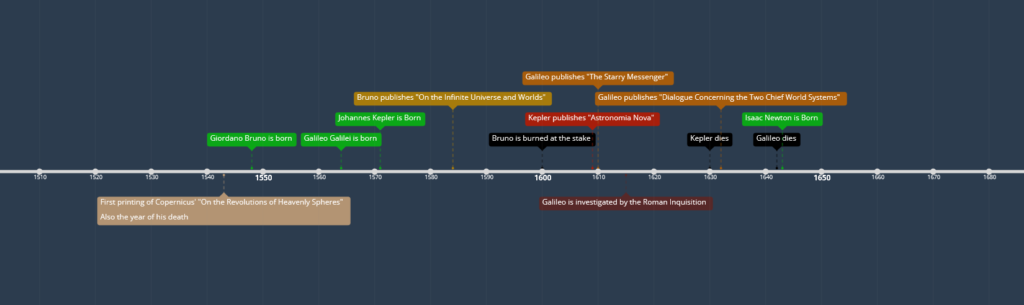

On this page, we’ll be looking mainly at the differences in how Giordano Bruno and Isaac Newton viewed God and God’s relation to the universe. Both of these philosophers wrote a lot about astronomy and their models as to how they thought the universe worked; as such, they do have a bit of overlap in terms of the specific fields they were interested in. However, one thing to keep in mind is the different contexts that they were writing (and by extension living) in. Newton was born in 1643, nearly a century after Bruno. This places them both solidly after Copernicus (with Bruno being born 5 years after his death) and his ideas of heliocentrism, in fact, Bruno references him quite often, like in The Ash Wednesday Supper. However, other science-philosophers like Kepler and Galileo would put out a lot of important work after Bruno’s death but before Newton’s birth, despite being alive at the same time as Bruno. Here’s a timeline to get a better visualization of what I’m talking about:

God: An Overview

Let’s start off by taking a general look at what God (and the universe) even meant to Bruno and Newton. Beginning with the former, for Bruno, God was infinite. In addition, the universe was derived from God, in the sense that all the “stuff” in the Universe contained essence of God. However, take note: “It was the universe, not the first Adam or…Jesus that was made in God’s image.” (Smith, 2008). Bruno “saw God as nature” (Candela, 1998). And in a Cavendish-like way, he appreciates not only nature, but also non-human organisms. He admits that in many respects, humans are not #1; specifically, he uses the examples of ants as a more intelligent species than humans due to their hive-minded nature.

Now onto Newton. Right off the bat, looking at his General Scholium, we see some differences with Bruno. Newton mentions the significance of God’s dominion over and over. “The supreme God, however perfect, without dominion, cannot be said to be Lord God.” And following from this, he claims “a God without dominion… is nothing else but Fate and Nature.” However, despite this apparent disagreement, it seems that they both agree on the idea that God is “in” everything. Newton’s idea of this comes once again from the General Scholium. “[God] is omnipresent not only virtually but also substantially; for action requires substance.” What does this mean? The idea here is almost that of a verb and a noun, or more accurately, a subject and a predicate. If I say “runs”, that doesn’t mean anything. But if I say “the dog runs”, that makes more sense. If we expand that to God and space: God is everywhere, and anything that happens is an action stemming from God (a “modification” of the God “substance” as Patrick Connolly puts it).

A Deeper Dive

What was written in the section above is obviously not the end all be all. Let’s examine a specific argument of Bruno’s that doesn’t appear really in Newton’s literature, not mentioned above. Specifically, a common theme that comes up with Bruno is his comparing of things in space to living organisms. This was mentioned in my rundown of Bruno’s general philosophy, specifically on his reasoning for orbits, but I’ll recap briefly. He viewed the relationship between planets and stars in an almost symbiotic manner, with stars feeding off the water of planets (he believed all planets had water). Bruno talks about the universe in a similar manner “The universe was like a ‘gastropod’, a living mass endlessly changing in configuration.” (Smith, 2008).

But, let’s put Bruno and Newton back together again. Newton makes the argument that space is God’s sensorium. Well what does that mean? It means that space is an organ of God, one that God uses to perceive but more importantly make decisions. In short, space is the medium by which God exercises influence. Well, okay, is that the same idea that Bruno has? With that specifically terminology (that of the sensorium), probably not. But even on a broader scale I would argue that they differ here. There is a difference between Newton’s argument that God is present everywhere and exercises his will everywhere and Bruno’s argument that the universe and the cosmos are essentially just God. However, the ambiguity that sometimes comes along with the nature of their writing but also the vocabulary they use (is Bruno’s nature = Newton’s nature?) doesn’t make things any easier to interpret. Nevertheless, There are some clear similarities between them, but also varying amounts of differences, depending on how you want to view things.

Sources

Smith, George. “Isaac Newton.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Fall 2008. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2008. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/newton/.

Connolly, Patrick J. “Newton and God’s Sensorium.” Intellectual History Review 24, no. 2 (April 3, 2014): 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496977.2014.914644.

Austin, William H. “Isaac Newton on Science and Religion.” Journal of the History of Ideas 31, no. 4 (1970): 521–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/2708258.

Candela, Giuseppe. “An Overview of the Cosmology, Religion and Philosophical Universe of Giordano Bruno.” Italica 75, no. 3 (1998): 348–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/480055.